October 12 saw the online launch for the book School Uniforms: New Materialist Perspectives (edited by Rachel Shanks, Julie Ovington, Beth Cross and Ainsley Carnarvon). This book brings together a new materialist approach to understanding how school uniform imposes performances that have a formative effect on young people’s identities and economic positionality. In Chapter 4, titled “Intervening in School Uniform Debates: Making Equity Matter in England “, our FEELers Dr. Sara Bragg and Prof. Jessica Ringrose, with contributions by Alison Wiggins, Kate Boldry and Amelia Jenkinson, discuss a community-engaged learning project at the Institute of Education. At the book launch, Alison Wiggins and the current CEO of School of Sexuality Education Dolly Padalia talked on behalf of the whole project team about what has been done in the project and its impact. This blog introduces the book chapter, drawing also on Alison and Dolly’s contributions at the launch.

Background: School uniform matters

‘

As educators, we come to realize through our experiences in schools that school uniforms have no direct bearing on learning or the concept of fairness through sameness. As we continue our work within schools and engage with young people, it becomes evident that the situation remains largely unchanged. It seems we are stuck in an era of middle-class British traditions in the UK, and an era that increasingly ignores the needs of today’s youth.

’

(Alison)

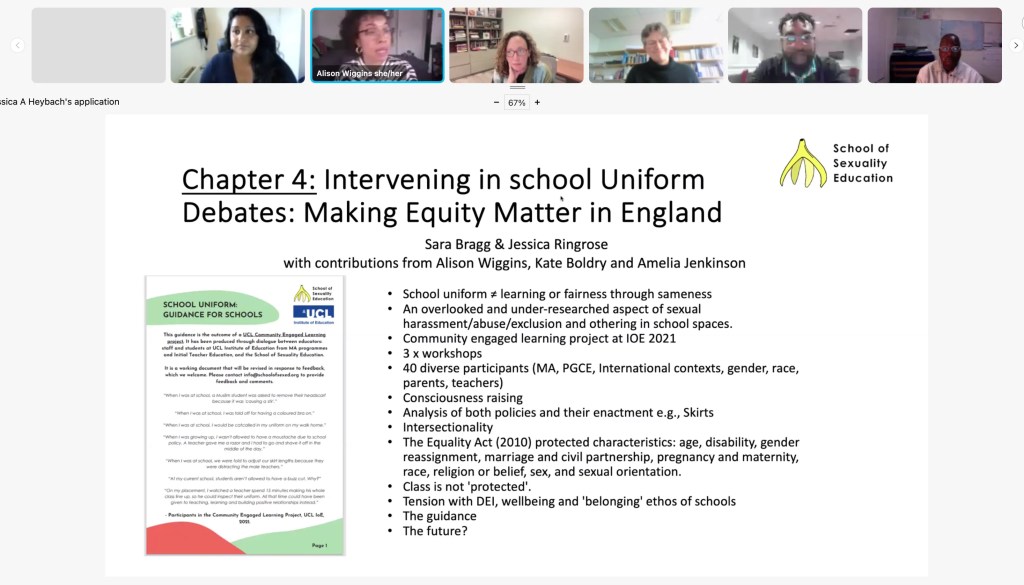

Strict enforcement of school uniform seems to be increasingly accepted as ‘common sense’ in some quarters and has raised debates among school leaders, parents and students on ‘fairness’, relation to learning, and costs. However, uniform policies and practices receive inadequate attention in relation to diverse students and a series of intersectional power relations-class, heterosexuality, race etc., as well as the ‘sex’-segregated uniform. As an attempt to extend the debates around school uniform policies and practices, the project discussed in the book chapter recognized that there is a strong and enduring relationship between the human and the non-human in school settings that goes far beyond the interactions that happen in schools, and understood that uniforms co-materialise power relations in school settings.

The project ran three online workshops with over 40 participants during the summer term of 2021, aiming to form critical connections between gender theory and school-based practice and to promote positive changes. Participants included student teachers, MA students from various gender-related programmes, lecturers and research staff, all of whom had experience in diverse school settings. The group also represented a broad international mix. While most of the participants identified as women, men and non-binary individuals from diverse contexts were also included. The first workshop encouraged participants to reflect upon their personal experiences about uniform when participants were at school, teaching in schools or their children going to school. The second workshop examined academic research and current school policies. The third workshop focused on developing insights and proposing policy recommendations to change and challenge inequities about both the policies themselves and about how those policies were enacted with young people.

Major Findings: Policing gender, intersectionality and uniform

Participants in the workshops discussed many ways that uniforms reinforce rigid, binary gender norms, and how this gives rise to problematic assumptions about sexuality and personal responsibility tied to these sexualities. For instance, skirt-wearing as a key marker of sexual difference has led to fetishization in various contexts, and the regulation of young women’s bodies has been done in ways that normalise harassment, sexism, sexual violence, and victim-blaming, contributing to a broader rape culture. Alison shared participants’ experiences of how skirt length was monitored and measured – some against rulers and sticks, some being required to kneel on the floor in front of teachers – on the grounds that shorter skirts would distract boys and men, implying a link between skirt length and the degree of modesty.

It was also observed that some teachers, even women teachers, would shame students wearing shorter skirts, suggesting abuse from men would be their fault and thereby blaming the victims, rather than addressing the perpetrators of harassment. Even where some schools outside the UK proposed alternative, loose sports-style uniforms, this was sometimes rationalised as preventing sexual harassment rather than promoting student comfort. Many participants shared how wearing compulsory skirts made them feel unsafe in certain spaces due to a hostile and hetero-patriarchal public sphere.

A key concern of the workshops was intersectionality, specifically the protected characteristics embedded in uniform policies and their enforcement, such as disability, diversity, gender reassignment, race, and religion. While class is not a protected characteristic, it emerged as a significant concern due to the middle-class default upon which uniforms are often based, and the economic implications associated with school uniforms, which have been highlighted in the media.

Impact: Guidance for schools and students

The project created guidance for schools outlining the harms and inequities of existing school uniform polices and advocating positive alternatives – in particular moving uniform from a ‘discipline’ issue to a ‘welfare, wellbeing and inclusion’ approach. This guidance is available on the School of Sexuality Education website and used by SSE in CPD training sessions. At UCL IOE it is integrated into teacher training session on topics like LGBTQIA+ inclusive spaces and sexual violence in schools.

Additionally, the project created advice for students around advocating for their rights, including tools to help them make their voices heard. This would help them understand that “what they were experiencing was not Okay, and it was not their fault”, as Dolly argued.

Some students and parents have reached out for support based on this guidance, often related to issues such as uniform violations or problematic uniform policy changes. The guidance also received a positive comment from Prof. EJ Renold at the book launch: “Awesome work!! I share this fabulous guidance with teachers all the time in Wales – and Wales has a statutory gender-inclusive uniform policy. So great to see this collaborative work making a difference.”

Overall, the guidance has proven invaluable, particularly in School of Sexuality Education CPD training sessions, and it is extending its impact beyond to provide some support for parents and carers who want to challenge and resist the harmful uniform policies and practices.

Future conversation: Keep challenging and questioning

At the end of the book launch, Alison highlighted the importance of preparing teachers to enter schools with critical thinking and the ability to question long-standing systems: “We’ve got to empower teachers to question and challenge some of the things that are in place that nobody really looks at, that just kind of gets repeated year on year. Policies that don’t work for children in schools are not policies that should remain.” This guidance is an opportunity to promote activism among academic staff, teachers, students, parents, and other stakeholders.

We have already seen changes taking place, and the guidance will continue to be a vital resource for further improvements. We need to challenge discriminatory practices, like school uniform. The future is about asking hard questions, challenging norms, and using the tools we have to make a positive change.

Blog author: Sitian Chen (edited by Sara Bragg)